Over the past 25 years, hundreds of millions of people have been lifted out of poverty, though often at the expense of the environment. What efforts are underway or could be implemented not only to achieve “green growth” but also to ensure that it is inclusive and equitable? This essay, part of the Middle East-Asia Project (MAP) series on “Transitioning to Inclusive Green Growth,” explores these and other related questions. More ...

Energy remains among the most strategic natural assets in the world economy and a fundamental basis for achieving and sustaining development goals. Countries around the world have built their development results on expanding access to energy and rising intensity of energy use, with energy security now a key factor in achieving national resilience. As we look to the future, two key mega-trends are catalyzing changes to the traditional energy security landscape, with important links to the development agenda.

The first is the rising energy demands from Asia’s emerging economies such as China and India, the new centers of gravity in terms of economic growth and energy demand. Global energy demand is set to increase by 30 percent by 2040, pulled in good part by emerging Asia; with China expected to see 85 percent energy demand growth to 2040 and India expected to see a 300 percent increase.[1] Coal use globally is expected to peak by this time, alongside a 50 percent rise in use of natural gas. Related to this is a projected $44 trillion of new investments in the energy sector, with 60 percent of this to oil, gas and other fossil fuel sectors and the 40 percent to renewables, energy efficiency and other sustainable energy solutions.

A second transformational shift is the ecological crisis facing the planet and the related move towards low-carbon models of development which are aimed at decoupling growth from rising energy intensity and keeping global temperature rise to below two degrees Celsius by the end of the century, in line with the Paris Agreement on Climate Change. Rather than a barrier to development, many developing countries are now engaging this green economy opportunity as a means of supporting emergence of their clean energy sectors, as a new high-tech added-value segment of their economy with benefits for local energy systems and export potentials. This is expected to result in continued rapid growth of the clean energy sector, including in countries such as China and India, which are already emerging as new clean energy superpowers.

These two shifts in the energy security landscape bring with them geo-strategic implications for the nature of energy diplomacy, trade, investment and development. As explored further below, this holds particular importance for new partnerships between emerging economies in Asia and oil- and gas-rich economies in the Middle East. The latter remains the world’s capital of oil and gas reserves, with its global share of these resources set to increase further in coming decades. Meanwhile the region also has one of the world’s fastest growth rates of domestic electricity use, a growing drain on local energy reserves bringing risks to export revenues which stand at the base of the region’s development model. This, together with world-leading levels of solar radiation, has recently generated an unprecedented series of national sustainable energy strategies across the region. As elaborated below, new partnerships are rapidly emerging between Asia and the Middle East to engage these trends — on the one hand to expand supply of Middle East energy to Asia, and on the other to expand clean energy technology and finance from Asia to the Middle East.

Sustainable Energy Pathways on the New Silk Road

The new energy security landscape is being shaped in particular by the rapid pivot of China to the Middle East.[2] This year marks the 25th anniversary of the launch of China’s socialist market economy policy, unleashing a new era of market based development in China and its rapid ascent to what will soon be the world’s largest economy. Trade between China and the Middle East surged 600 percent from 2004-2014, with China having surpassed the United States in 2015 as the leading destination for Middle Eastern oil. Currently, more than half of China’s oil imports originate from this region. China’s overall bilateral trade flows with Egypt, Iraq, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and U.A.E. have expanded dramatically. China has further emerged as a clean energy leader, leading globally in terms of new installed capacities domestically, and hosting some of the world’s largest solar and wind technology companies now expanding their investments and partnerships in the Middle East.

To elaborate the full potential and contours of this emerging partnership, including but going beyond the oil and gas trade, 2016 saw issuance by China’s State Council of an Arab Policy Paper — outlining a foreword looking vision of where the emerging partnership could go in coming decades.[3] It highlights a “1+2+3 approach” including (1) energy cooperation around oil and gas sectors serving as the core of the aspired China-Middle East partnership, (2) infrastructure, trade and investment as parallel enabling actions, and (3) a set of forward-looking breakthrough initiatives including sustainable energy solutions to support innovation and diversification. This three-pillar approach is well aligned to the above-noted drivers of the new energy security agenda and sets the prospects of China-Middle East energy cooperation on a broad footing.

In operationalizing China’s new Middle East partnership strategy, a key platform will be the new $1 trillion One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative, a vehicle for catalyzing a New Silk Road through infrastructure and investment partnerships in over 60 countries. This includes key partner countries in the Middle East which have served historically as key cross-roads of trade and investment between Europe, Asia and Africa. The implementation of OBOR would be supported by the $40 billion New Silk Road Fund, the $100 billion Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), China’s $750 billion sovereign wealth funds and its more than $3 trillion of foreign exchange reserves.

OBOR stands as one of the most ambitious development projects in modern history, carrying within it great potential as well as strategic risks. In line with China’s new Middle East strategy, OBOR is expected to support a rapid expansion of conventional energy trade and investments, particularly regards natural gas. Initial examples of ongoing and prospective partnerships along the Silk Road include:[4] the $10 billion China-Central Asia Gas Pipeline, the $46 billion Gwadar LNG Terminal and Pipeline, the Yanbu Refinery in Saudi Arabia and a series of investments into gas-fired power plants including in Egypt and U.A.E.

While cooperation proceeds along these lines, there are a number of risks to consider, particularly regarding issues of inclusion and equity. Across the Middle East, calls have arisen in recent years for a new social compact centered on more transparent, accountable and participatory governance of the region’s energy wealth. The energy sector in the region has faced many challenges in terms of engaging local citizen access and benefit-sharing, a long-standing grievance among local communities in many countries. In addition, many extractive ventures have seen an expansion of toxic impacts on people and ecosystems.

Given the status of the Middle East as the planet’s most water insecure region and very limited arable land, emerging oil and gas investments under OBOR should devote adequate attention to social and environmental safeguards. While the New Silk Road Fund has yet to issue its social and environment standards, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) has conducted public consultations in recent years for design of its new Environmental and Social Framework. Under this policy, AIIB is meant to undertake free, prior, and informed consultation during development of investment projects. Through cooperation with local partners and international bodies, an opportunity exists for new oil and gas investments to avoid many of the negative impacts generated by foreign investments globally. Many lessons and good practices have been generated on use of social and environmental standards in development.[5]

A second important opportunity exists in mobilizing China’s new Middle East strategy and OBOR for scaling-up of sustainable energy results. The Middle East is seeing some of the world’s fastest growth rates in electricity consumption,[6] and with most power generated from fossil fuels, this is becoming a large drain on energy reserves that could otherwise be used for export revenues. Should current rates of energy intensity growth continue, hundreds of billions of dollars in oil and gas export revenues would be foregone. This now serves as a major economic driver of change, catalyzing the ascent of renewable energy and energy efficiency solutions up the policy agenda in the region, with a number of countries setting new national strategies and some of the world’s most ambitious sustainable energy targets.[7]

Partnerships with China on the sustainable energy agenda via OBOR and other platforms would be a strategic opportunity to achieve the type of breakthrough innovations called for under China’s new Arab Policy Paper. China has become a world leader in sustainable energy solutions, with its solar technology global exports reaching $174 billion from 2003-2013; 44 percent of the global total.[8] Large scope exists for South-South technology and finance cooperation to help achieve the new sustainable energy targets in the Middle East, building on China’s successes in scaling-up solar and efficiency solutions domestically and globally. The Green Ecological Silk Road Investment Fund launched by China in 2015 could also be an important support in this regard, with initial capitalization of $4.8 billion by a group of Chinese firms and in partnership with the United Nations. Cooperation on solar and efficiency can emerge as a win-win output of the New Silk Road, helping bring about social, economic and environmental results.

Emerging Bottom-Up Solutions

While trade and investment around conventional energy resources is expanding rapidly, it is the clean energy track of partnership under China’s Middle East strategy and OBOR where greater progress is needed and where inclusive, green economy approaches in concert with the United Nations and other partners can add value. A few examples follow where South-South cooperation could be explored.

A key axis in the emerging New Silk Road will be Egypt’s Suez Canal, a historically critical channel for trade and energy flows between Asia, Africa and Europe, as well as a new and strategic point of partnership between China and the Middle East. In recent years Egypt has launched plans for a New Suez Canal Zone, an attempt to expand and diversify the nature of infrastructure and economic activity around the Suez Canal for benefit of local growth as well as expanded trade between Asia, Africa and Europe. In recent years Chins and Egypt have attempted to scale-up their bilateral partnership, with trade having nearly doubled between 2009-2014 to $11.6 billion, and with high level 2016 bilateral meetings between Heads of State resulting in a series of new bilateral agreements and plans for $15 billion of new investments into Egypt in including expansion of cooperation in the New Suez Canal Zone (SCZone) initiative, from $400 million to $2.5 billion.[9] China is a strategic partner to the SCZone, building off its own experiences in using special economic zones as a basis for development. As the new partnership emerges, an opportunity exists to position sustainable energy technology as one of the strategic sectors for emergence of the SCZone, helping generate within SCZone a ‘green economic zone’. In addition, Egypt as the largest country in the Middle East seeks to expand energy access for the poor, with a new partnership emerging with China’s Yingi Solar company to jointly development with local partners a new 50 GW solar facility for local energy access. Further scaling up south-south cooperation for energy access can be of great benefit as Egypt seeks to pursue inclusive, green models of development under its national sustainable development and energy plans.

Further east, neighboring Saudi Arabia is also one China’s key strategic allies in the region as the New Silk Road emerges. Beyond the central role of the Kingdom’s vast oil reserves in the Asia partnership, under its Vision 2030 strategy Saudi Arabia now has one of the region’s most ambitious sustainable energy expansion plans, including a major focus on expanding energy efficiency measures. For example, through a $36 million National Energy Efficiency Programme between UNDP and the Saudi Energy Efficiency Centre, the capacity of local partners are built to take action on sustainable energy solutions. One of UNDP’s largest sustainable energy projects globally, the partnership has helped local partners design new energy efficiency policies, action plans to reduce energy intensity of growth in key sectors, convening public-private partnerships, and raising awareness among leaders and the public on the development benefits of clean energy solutions. Taking results to the next level in concert with emerging partners in Asia, such as China, can be of great benefit to build on China’s significant energy intensity reductions in recent years, as Saudi Arabia moves ahead with its ambitious, potentially transformational sustainable energy strategy.

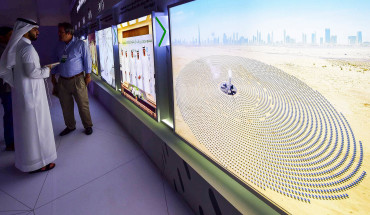

Last but not least, the United Arab Emirates (U.A.E.) has emerged as one of China’s most strategic partners not just in the Middle East but globally. The emerging role of Dubai as a hub of private sector innovation and finance is matched with a new ambitious target to reach 30 percent renewable energy in the national energy mix by 2030. China is already playing a role in initial achievements. In 2016, the U.A.E. set a new world-record 2.4 U.S. cents per kWh solar power tariff price for the planned Sweihan solar park in Abu Dhabi, slated to be the world’s largest once completed around 2019. The leading Chinese solar firm, JinkoSolar, and the Japanese solar developer, Marubeni, jointly led the winning bid, with the Indian firm, Sterling and Wilson, spearheading engineering, procurement and construction. With a planned capacity of over 1,000 megawatts and a budget over $800 million, once completed in 2019 the Sweihan solar park will be the world’s largest solar park.

China’s role as a global leader in solar development is starting to emerge and can further expand to become an important part of the New Silk Road process. A potentially important platform in this regard for emerging China-Middle East energy partnerships is the World Green Economy Summit which Dubai hosts annually in partnership with UNDP and other strategic partners. At the 2016 edition of WGES, a plan was launched by U.A.E. leaders to establish in Dubai a new World Green Economy Organization (WGEO) in coming years. Through a new $11 million technical assistance project launched in 2017 between Dubai partners and UNDP, WGEO would be established in coming years as a new platform for innovation, finance and private partnerships. In September 2017, WGEO launched its global financial sector platform at the UN premises in China, in recognition of China’s leadership in green finance domestically and the important role of AIIB and other mechanisms in promoting south-south cooperation. Through partnerships with public and private leaders in countries like China, WGEO could support new breakthough innovations and serve as a catalyst and accelerator for South-South cooperation towards green, low-carbon development across the South.

Conclusion

Emerging Asia’s outward expansion can be an opportunity to catalyze new levels of development in partner countries in the Middle East as it seeks to recover from a period of unprecedented crisis. Promoting transparency, accountability and participation in local decision-making and review of new oil and gas investment proposals in host countries would support goals of poverty reduction and inclusion. This would help reduce risk of social grievances and protests that have emerged all too often in recent years around the world regards new energy and infrastructure investments. Promoting scale-up of renewable energy and energy efficiency investments would support green economy goals and countries’ newly launched sustainable energy strategies meant to reduce the energy intensity of development in the region. This can build on many recent success stories and lessons learned in Asia as the Middle East seeks to diversify beyond oil and gas and engage its vast solar potential.

The emerging partnership between Emerging Asia and the Middle East holds both challenges and opportunities for future development pathways. OBOR and other processes will in coming years lead to emergence of a New Silk Road, returning China and other parts of emerging Asia to their historic place at the center of the world economy. Visionary leadership will be needed to manage risks, create development dividends from this process, and generate new inclusive, green development pathways for benefit of people and planet.

Note: The views and opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the United Nations, UNDP or its Member States. Appreciation is noted for peer review of this article by Stephen Gitonga, UNDP Regional Energy Specialist and Walid Ali, UNDP Regional Climate Change Specialist.

[1] International Energy Agency (IEA), World Energy Outlook (Paris: International Energy Agency, 2016).

[2] See Mirek Dusen and Maroun Kairouz, “Is China pivoting towards the Middle East?” World Economic Forum, April 4, 2017, accessed September 1, 2017, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/04/is-china-pivoting-towards-the-middle-east/.

[3] For the full text, see “China’s Arab Policy Paper,” Xinhua, January 13, 2016, accessed September 1, 2017, http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2016-01/13/c_135006619.htm.

[4] Criselda Dialia-McBride, “OBOR and the future of energy trade,” Eniday.com, accessed September 1, 2017, https://www.eniday.com/en/sparks_en/obor-china-global-energy-map/.

[5] For example, see generally United Nations Development Program (UNDP), “UNDP’s Social and Environmental Standards,” accessed September 1, 2017, http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/operations/social-and-environmental-sustainability-in-undp/SES.html.

[6] Regional Center for Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency (RCREEE) and UNDP, Arab Future Energy Index (AFEX) Energy Efficiency Report (RCREEE), Cairo, 2017, analyzing and ranking country trends in energy intensity growth and efficiency policies.

[7] See generally RCREEE and UNDP (2016) Arab Future Energy Index (AFEX) Renewable Energy Report, RCREEE, Cairo, analyzing and ranking country-level trends regarding expansion of renewable energy policies and solutions across the region.

[8] John A. Mathews and Hao Tan, “China’s New Silk Road: Will it contribute to export of the black fossil-fueled economy?” Asia-Pacific Journal 1-8 (2017): 4, accessed September 1, 2017, http://apjjf.org/2017/08/Mathews.html.

[9] Mordechai Chaziza, “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership: A New Stage in China-Egypt Relations,” Middle East Review of International Affairs (MERIA) 20, 3 (2016): 43-44.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.