Various Track Two approaches to peacebuilding in the Middle East have been pursued through ecumenical dialogue and educational programs such as The University of the Middle East Project.[1] Yet the direct use of environmental conservation as a mutually agreeable way to approach territorial conflict resolution has thus far not been seriously deliberated. Some “realists” might be dismissive of such a prospect, but the concept of “peace parks” has shown practical promise in resolving territorial disputes. Warring parties can be made to realize quite pragmatically that joint conservation is economically beneficial and also a politically viable exit strategy from a conflict.

The US used such a strategy in the mid-1990s to resolve a decades-old armed conflict between Ecuador and Peru in the Cordillera del Condor region.[2] The Obama Administration’s deputy envoy to the Middle East, Fred Hof, proposed the Golan “peace park” effort as a means of peacebuilding with Syria in a formal paper written for the US Institute of Peace in 2009.[3] In Hof’s plan, water guarantees to Israel (which currently gets 30% of its water from the region) could be exchanged for return of sovereignty to Syria. Syrian-American negotiator Ibrahim Suleiman and former Director-General of Israel’s Foreign Ministry Alon Liel discussed this prospect in 2007 when they met with the Israeli Knesset’s Foreign Relations and Defense Committee to develop a plan to establish a jointly administered peace park between Syria and Israel in the Golan.

The Golan Setting

The original Druze inhabitants of the region see themselves as distinct from Israelis and Palestinians since their religious group has its own culture and ethnic identity. The Golan Heights has a population of about 38,900, of which 19,300 are Druze, 16,500 are recently settled Jewish immigrants, and about 2,100 are Muslim. The Golan is also an environmentally sensitive region with a cool and moderately wet climate that has allowed fruit orchards to flourish. Underscoring the unique environmental conditions of this area, Israel has allowed Druze farmers to export some 11,000 tons of apples to Syria each year since 2005.

This confluence of interests makes the region an ideal case for implementing a novel dispute resolution strategy known as “environmental peacebuilding.” The strategy involves transforming disputed border areas into transboundary conservation zones with flexible governance arrangements. Such territorial arrangements are increasingly called peace parks.

To some commentators, this term may suggest idealistic or naive notions of conflict resolution, but it is championed even by military officers, such as retired Indian Air Marshal K.C. “Nanda” Cariappa, a former POW who has called for such a strategy to resolve India and Pakistan’s dispute over the Siachen Glacier.

The proposal was initially motivated by Robin Twite’s work at the Israel-Palestine Center for Research and Information during the 1990s. Now the strategic plan for the effort has been laid out in detail and there is momentum to move forward on this solution, which is feasible in the Golan, given the demographics of the region. According to one plan, Syria would be the sovereign in all of the Golan, but Israelis could visit the park freely, without visas. In addition, territory on both sides of the border would be demilitarized along a 4:1 ratio in Israel’s favor.

Two-sided ski resort? Skiing for peace?

The spectacular Mount Hermon area could be of particular conservation and recreational importance. Herer Israelis and Syrians could visit without visas, but when exiting this special zone visas would be required. Israel already has a major ski resort on one side and Syria is planning to build a resort on its side of the divide. The summit of Mount Hermon is still under Syrian sovereignty, and including this in the proposed peace territory would give Israelis an incentive to also come to the negotiating table since it would give them friendly access to a unique ecological region. This would be similar to the status of the eastern Sinai under the Israeli-Egyptian peace treaty and also similar to the status of Hong Kong and Macau in China whereby there are separate entrance concessions for these areas as compared to mainland China.

When one examines the status quo between Israel and Syria over the Golan Heights, it is clear that neither side is willing, at present, to relinquish its claim to this vital region. Syria has a legitimate claim on the basis of recent history, while Israel has a claim based on the ruins of 29 ancient synagogues and perhaps more consequentially as a security buffer. As argued by Rabbi Michael Cohen of the Arava Institute for Environmental Studies,[4] “one way to break through this stalemate of legitimacy is to phrase the dynamic in a different way. That is to say, it is not so much that Israel wants to keep the Golan Heights, but that they don’t trust giving the Heights back to Syria.”

This understanding of the dynamic opens up possibilities for a new scenario whereby a third party is involved. In addition to the peace park proposal, it is also possible to set up a Druze Autonomous Area that is neither Israeli nor Syrian but jointly administered by a commission.

Similar proposals have also been initiated by Friends of the Earth Middle East[5] along the Jordan River, where there is already a “peace island” that Israelis and Jordanians can visit without visas and where the original peace treaty between the two countries was signed and is currently under deliberations for expansion.

This case is particularly intriguing since, under the treaty, there is an Israeli kibbutz which is allowed to grow crops on Jordanian sovereign territory. A Yale University architecture class has already been working on the design of the expanded park in collaboration with neighboring Jordanian and Israeli communities. There is also a marine peace park agreement between Jordan, Israel, and Egypt in the Gulf of Aqaba (which was established as part of the first round of Oslo negotiations). The Golan proposal is geographically much more significant in terms of its joint-management potential and also as a means for instrumental conflict resolution between two states that currently do not recognize each other.

Opponents and Proponents of Land-for-Peace

A conference on the proposed peace park effort, held at Tel Aviv University in January 2010[6] showed that the fractures are still quite acute. On one hand, there was a speaker from the “settlers association of the Golan” who fervently opposed any land for peace. On the other hand, there was a resident farmer and academic scholar from the Golan Heights, Yigal Kipnis, who expressed a willingness to relocate if peace involved giving land back to Syria in exchange for security and joint environmental monitoring. Academics were also highly polarized in their approach to the issue, with some resurrecting ancient narratives of Judaic habitation in the area and others acknowledging that under international law the territory is definitely “occupied.”

As the Obama Administration considers its legacy in the Middle East, it should give priority to the Golan conflict and creative approaches to conflict resolution. Using the environment in this context is very promising but we must also be cautious and appreciate that conservation has also been used historically as a means of land appropriation.

Arabs are highly suspicious of conservation efforts in this context, just as Native Americans have been suspicious of the US National Park system, whose establishment often excluded them from their land. Thus, any peace park must be one where access and economic development are concurrent with conservation. At the same time, the resolution of the Golan conflict cannot be considered in isolation from the Palestinian issue for too long. Ultimately, to cement lasting peace the Palestinian issue will also need to be resolved. Otherwise, the peace between Israel and Syria might end up being just as cold as the one between Egypt and Israel has become of late.

Treaties and Regional Mechanisms

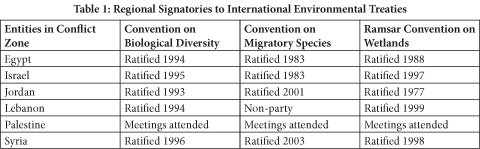

A means of strengthening environmental cooperation and peacebuilding through international means which have thus far not been used extensively are existing treaties to which countries in this region are signatories. By linking the use of transboundary conservation to conflict resolution through such treaties, we can also provide greater resilience to any agreements.

Table 1 provides a list of some of key environmental treaties and the status of regional signatories to these agreements which could be used constructively towards transboundary conservation initiatives. The countries and territories in the immediate border proximity of Israel are considered for the purposes of this analysis, given the potential for physical transboundary conservation.

In addition to these treaties, regional agreements based on ecosystem conservation that could be expanded to build trust as well include the Programme for the Environment of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden (PERSGA), which was initiated by the Arab League and the United Nations Environment Programme in 1974 but has thus far not included all countries bordering this ecoregion for political reasons. The United States has tried to facilitate cooperation over the Gulf of Aqaba between Israel and Jordan through the “Red Sea Marine Peace Park” (RSMPP) effort. Continuity and linkage to long-standing conflicts is important for cooperation of such programs even between countries that recognize each other diplomatically. Ultimately, ecology defies political borders and the governments of the Middle East will need to become aware of this natural reality which can ultimately lead to lasting cooperation.

[1]. University of the Middle East Project, http://www.ume.org/home.

[2]. C.F. Ponce and F. Ghersi, “Cordillera del Condor (Peru-Ecuador),” http://www.tbpa.net/docs/WPCGovernance/CarlosPonceFernandoGhersi.pdf.

[3]. Frederic C. Hof, “Mapping Peace between Syria and Israel,” United States Institute of Peace Special Report (March 2009), http://www.usip.org/files/resources/mappingpeace.pdf.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.