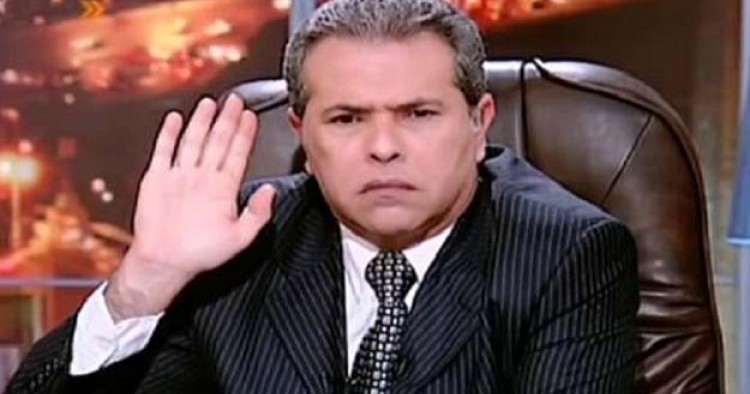

The Egyptian media landscape both before and after Hosni Mubarak’s ouster has been one in which the polemical television personality Tawfik Okasha has thrived. But Okasha, known for his conspiracy theories and strident rhetoric, particularly against the Muslim Brotherhood, has perhaps risen to greater fame and influence recently. With a convergence between anti-Brotherhood positions and Egyptian government policy and public opinion occurring since the mass protests that culminated in Mohamed Morsi’s removal by the military on July 3, Okasha’s views have become more mainstream. And though Okasha found himself taken off the air last month after he directed his rhetoric against the new government, he has recently returned. The rise (and intermittent falls) of such a figure allows a glimpse into the disorder and polarization that have characterized Egyptian media over the past several years.

Okasha, a dour-looking man in his late 40s, left his job as a presenter on the state-owned Channel 1 in 2009 to establish a new satellite channel, Faraeen. He and his cabal of acolytes presented a variety of programs that never strayed far from the theme that Egypt, “the greatest country in the world,” was under threat from foreigners, namely Americans and Israelis (and the Freemasons among them) who were infiltrating governments in Egypt and elsewhere in order to take over the Middle East. According to Okasha, only the Egyptian army—“the oldest and best in the world”—could, with his assistance, save Egypt. Okasha also devoted large segments of his programs before the revolution to censuring the April 6 Youth Movement, which he maligned as a foreign-funded, fifth column group of troublemakers.

His appearances became the stuff of legend. Similar to his American counterpart, the shrill television and radio host Glenn Beck, he presented half-baked conspiracies and plots that lacked factual evidence and were based in realities far removed from this one. He frequently invoked his rural Delta roots to excoriate his foes or to illustrate a point; in one program he suggested that his archenemy, Mohamed ElBaradei, who he described as an Israeli agent and Freemason, was not fit to be a participant in Egyptian affairs because he does not know how to force-feed a duck. In another program he proudly announced that all but one of Faraeen’s staff hailed from the Lower Egyptian countryside. He thus presented himself as the everyman who, when not bellowing out invectives in his studio, spent his time discussing agrarian affairs with farmers.

This mix of nationalist chauvinism and paranoia proved a successful formula. While Okasha has claimed that Faraeen enjoys 300 million viewers in Egypt and the Middle East—a most probably inflated figure that is impossible to verify—he and his channel have acquired a notorious celebrity and are household names in Egypt.

After the revolution, Okasha’s rhetoric appealed to the fears of many Egyptians buffeted by the winds of political change and whose lives were turned upside down in January 2011. Okasha’s emphasis on the importance of reestablishing security was a safety blanket for a public who had grown sick of the violence, turbulence, and uncertainty that followed the revolution.

Okasha began to focus on the Muslim Brotherhood when the group’s star rose and Morsi was elected president. Due to his strident speechifying against the Brotherhood, the Morsi-led state shut Faraeen down in 2012 pending investigations concerning charges that Okasha had incited his viewers to kill Morsi. The charges were dropped in January 2013, and Okasha went back on the air.

It was at this point that a convergence occurred between Okasha’s theories—hitherto regarded by all but his hardcore fans as the slightly crackpot musings of an eccentric—and public attitudes toward a revolution gone astray. This convergence tells us more about the failures of the revolution than it does about any prescience on Okasha’s part. Okasha’s misgivings about the Brotherhood were shared by a large proportion of the population even before the group assumed power. In office, the Brothers proved to be incompetent, intransigent, and bent on authoritarianism, and, as the security and economic situation worsened, Okasha’s repeated dark warnings about a Brotherhood-Hamas-Iranian triumvirate with plans to turn Egypt into a state controlled by foreign governments and Zionist intelligence agencies gained traction in mainstream media. Similarly paranoid ideas increased on other channels and in newspapers, such as claims of U.S. plots to aid the Muslim Brotherhood in spreading chaos, the presence of Syrian refugees in pro-Morsi sit-ins, and the involvement of Hamas in Sinai’s instability.

Then, after Morsi’s ouster on July 3, Faraeen’s brand of hyper-nationalism, which had always set it apart from the media pack, became even more in line with the mainstream. The summer months of 2013 on private satellite channels featured diatribes against the Brotherhood and Islamists in general, interspersed with eulogies for the military and praise for its chief, Abdul Fattah el-Sisi. “Egypt fights terrorism” banners in Arabic and English appeared on screens. The airtime of high-profile human rights activists was slashed dramatically. Such rhetoric was the bread and butter of Faraeen.

Though Okasha had called el-Sisi a secret member of the Muslim Brotherhood when Morsi replaced Defense Minister Mohamed Hussein Tantawi with him in August 2012, Okasha changed his tune after July 3. He even produced a documentary film called The Two Men that was repeatedly aired on Faraeen.

The documentary credited el-Sisi and Okasha for laying the groundwork for the June 30 revolution, thwarting attempts by the Brotherhood and foreign powers to take over Egypt. The 20-minute segment produced by Faraeen highlighted Okasha’s efforts to overthrow the Brotherhood amidst its alleged attempts to crack down on him through the closure of his channel and a number of legal complaints filed against him. It also credited Okasha with rallying millions of Egyptians to protest on June 30 against Egypt’s “state of defeat,” brought about by the Muslim Brotherhood and its alleged coordination with U.S. and Zionist intelligence services.

And yet, Okasha diverged from the new mainstream of army adoration, too, displaying a certain fluidity, if not inconsistency, in his positions. After the appointment of the interim prime minister, Okasha told viewers that Hazem el-Beblawi was a “liberal version of the Muslim Brotherhood” and that 17 of his ministers were carefully coordinating with American and other foreign Freemason groups. Okasha charged that el-Sisi was not cracking down hard enough on these groups, and presented him with a vague one week ultimatum to “cleanse” Egypt of the fifth column. The ultimatum was one of many issued by Okasha and was ostensibly ignored by the authorities.

However, the current Egyptian government then cracked down on Okasha as well. The Ministry of Investment shut down Faraeen in mid-September for violating the media code of honor, in particular for “offending the values of society,” “disturbing the community,” and “driving a wedge between national forces.” Faraeen went black, silencing Okasha and his one-man crusade against mysterious and nefarious foreign forces.

But the channel returned after roughly three weeks, with Faraeen broadcasting an uncharacteristically apologetic message to its viewers, promising to abide by the media code and respect state institutions. Though Faraeen’s return came with this apology, Okasha and other presenters have simply continued the rhetoric typically displayed on the channel.

Government authorities will be unable to push such rhetoric to the margins of Egyptian media unless they can implement a fair code consistently across channels. Yet the media crackdowns that have shuttered pro-Morsi channels in parallel with the reinstatement of Faraeen indicate that the government is using the “media code” to implement its politically-motivated media oversight. Such policies work in favor of Okasha and his ever-changing viewpoints.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.