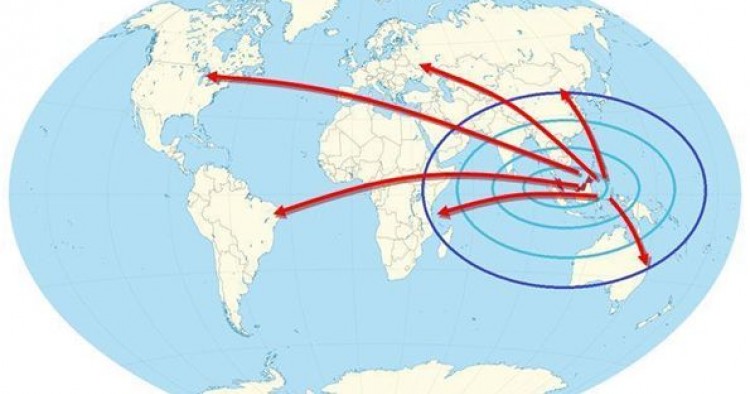

Strong energy demand in Southeast Asia is contributing to the shift in the global energy system’s center of gravity from West to East[1] ― a phenomenon that Malaysia is trying to capitalize on. In addition to being the region’s second largest oil and gas producer and the world’s second largest exporter of liquefied natural gas (LNG), Malaysia is located along the seaborne energy trade channel that binds together the Indian and Pacific oceans. Yet the country—and indeed Southeast Asia as a whole—is facing a looming energy challenge, as rapidly increasing energy use has led to a sharp rise in dependence on oil imports and a decline in the surplus of natural gas for export.[2]

Under these circumstances, Malaysia is trying to leverage its strategic location to make a virtue of necessity. The government of Prime Minister Najib Razak has embarked on an ambitious effort, spearheaded by state-owned Petronas (Petroliam Nasional Bhd), to transform Malaysia into a major maritime energy hub and revitalize the oil and gas (O&G) sector.[3] This essay discusses the major steps that Malaysia has taken in pursuit of these goals and the ways in which Malaysia-Gulf Arab energy relations have changed as a consequence.

The O&G Sector in Malaysia's Future

The O&G sector constitutes roughly one-fifth of Malaysia’s GDP and is listed as one of the 12 critical sectors for growth in the Economic Transformation Program (ETP).[4] As such, it is a pillar of the government’s program to lift Malaysia into the ranks of high-income countries.[5] Since the launching of the ETP in 2010, efforts have been made on multiple fronts to invigorate the O&G sector.

1. Increasing Aggregate Oil Production Capacity

After three decades of extensive production, Malaysian oilfields have entered their mature phase. To arrest declining production, Malaysia is seeking to rejuvenate existing fields through enhanced oil recovery projects implemented under production sharing agreements and the more recently introduced mechanism of risk sharing contracts (RSCs).[6] The expectation is that these measures will extend the life of existing fields and lead to increased oil production.[7] In January 2012, Petronas and Shell agreed to invest $11.46 billion over a 30-year period to recover oil off Sarawak and Sabah.[8] The Tapis field—a collaborative effort between Petronas and ExxonMobil and the first large-scale enhanced oil recovery project of those announced under the ETP—is on track to deliver first oil by the end of 2014.[9]

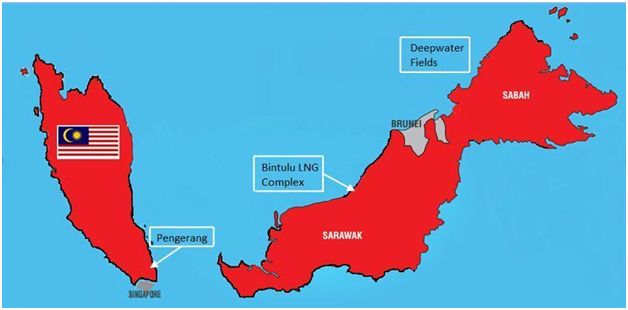

Falling production in current fields has also spurred efforts to develop deepwater fields. Although Malaysia has the third-largest oil reserves in Asia (after China and India), a large swath of its potential hydrocarbon acreage remains unexplored. The hope is that if substantial oil deposits were to be found and extracted, Malaysia could further delay depletion of its reserves, attract technical expertise, move up the technology curve, and facilitate the transfer of technology.[10] With its renewed focus on boosting domestic reserves and production, Petronas, which is vested with responsibility for developing and adding value to the country’s O&G resources, is spearheading efforts to do just that.

Sabah, a focal point of these efforts, has become one of the region’s deepwater exploration hotspots.[11] In November 2012, Shell Malaysia announced early production from the Gumusut-Kakap deepwater field[12] and is leading a consortium to develop Malikai. Both fields are located off the shore of Sabah,[13] as is Limbayong gas field, where Petronas and its partners Shell Malaysia and ConocoPhillips announced the discovery of oil-bearing sands in March 2014.[14]

2. Growing the Downstream Industry

Two decades ago, Malaysia had to depend on the refining industry in Singapore to meet domestic demand for petroleum products. However, after having invested heavily in refining activities, Malaysia is now able to fulfill its own requirements.[15] The hope is that by further increasing its oil-refining capacity, Malaysia could tap into the business of refining shipments of oil that pass through the Straits of Malacca for export to other Asian markets.

Operating mainly from the manufacturing complexes at Gebeng, Kertih, and Pasir Gudang, Malaysian companies produce a wide range of petrochemical products. Recently, though, in accordance with the strategy developed under the ETP, Petronas has sought to diversify Malaysia’s product base and move the country into the premium value and specialty chemicals market. There has been some progress in this area (e.g., the agreement between the German chemicals giant BASF and Petronas to expand their joint venture by building an integrated aroma ingredients complex in Gebeng Industrial Park).[16]

3. Developing O&G Services and Equipment Manufacturing Capacity

The Malaysia Petroleum Resources Corporation (MPRC), a unit within the prime minister’s office, is tasked with facilitating the growth of O&G services. The MPRC has set itself the ambitious goal of tripling the sector’s contribution to the economy.[17] Achieving this goal will require the participation of well-established foreign firms and local companies. A number of leading foreign oilfield service and equipment companies have been drawn to Malaysia,[18] because many of their customers—small- and medium-sized companies as well as major foreign operators—are based there.[19] Joining forces with them are a clutch of competent local O&G services firms such as Scomi, SapuraKencana, Petra Perdana, and Wasco, which have benefited from strong state support.[20]

4. Expanding Petroleum Storage and Trading

Although Malaysia already has oil storage terminals at Tanjung Bin, Tanjung Langsat, and Pasir Gudang,[21] it plans to treble capacity by 2017 in order to meet the expected growth in demand, mainly from China and India but also from the rest of Southeast Asia.[22] The MPRC has instituted a Global Incentives For Trading (GIFT) scheme[23] aimed at enticing major oil trading firms to relocate their trading desks to Malaysia. Vitol, the world’s largest independent oil trader, has enrolled,[24] as have BB Energy of the United Kingdom and 13 other oil trading companies.[25]

5. Developing LNG Trading Capabilities[26]

The number of LNG-importing markets continues to grow.[27] Within Asia, LNG is expected to play a larger role in meeting the growing demand in the region for efficient and cleaner energy. Malaysia is grappling with how to exploit the opportunities presented by these trends, given its current production capacity and rising domestic requirements.

Malaysia is the world’s second-ranked LNG exporter after Qatar. To date, the Bintulu Liquified Natural Gas Complex on Sarawak, the world’s largest LNG production facility, has served as Malaysia’s main vehicle for supplying its primary customers: Japan, Korea, and Taiwan. Recently, however, in an effort to rectify regional gas imbalances within Malaysia while meeting export commitments, Petronas has made a series of capital-intensive LNG investments.[28] These investments include a number of infrastructure projects designed to prepare for the impending shortfall of supply in Peninsular Malaysia, notably an LNG regasification terminal located offshore near the port of Sungai Udang in Malacca.[29] Petronas has also commissioned the construction of two floating gas (FLNG) facilities, the first scheduled for deployment in 2015 and the second in 2018. These facilities will enable liquefaction, production, and offloading processes to be carried out in remote offshore gas fields, which otherwise would be uneconomical.

Construction of the Sabah Oil & Gas Terminal, the first integrated O&G terminal in Malaysia, is also well underway. When it becomes fully operational, this terminal will receive, handle, and export gas (and oil) produced in offshore fields in Sabah. It will also complement the Sabah Gas Terminal, Labuan Crude Oil Terminal, and the Labuan Gas Terminal.[30] Meanwhile, on the international front, Petronas has been angling to enter Canada’s fledgling Pacific Northwest LNG sector.[31]

Pengerang: From Fishing Town to O&G Hub

The Pengerang Integrated Petroleum Complex is the showpiece of Malaysia’s efforts to establish the country as a regional energy hub and thereby help drive economic growth. This mammoth project, which is being built on a 20,000-acre plot of reclaimed land overlooking the Straits of Singapore and the South China Sea, is composed of two mega-projects: the Pengerang Independent Deepwater Petroleum Terminal, and the Refinery and Petrochemical Integrated Development (RAPID) and associated facilities complex.

The Deepwater Terminal project—undertaken by a public-private consortium led by Dialog Group in partnership with Dutch Royal Vopak of Netherlands and State Secretary Johor, Inc. (the investment arm of the Johor state government)—will provide storage, blending, and distribution services for crude and petroleum products.[32] The facility began operations in April 2014 when it received its initial fuel shipment, thereby becoming the first commercial oil terminal in Southeast Asia to offer crude oil storage.[33]

When it is completed, the Petronas RAPID complex will house oil refineries, naphtha crackers, and petrochemical plants, as well as facilities for the storage, loading, and regasification of LNG for both trading and domestic use.[34] According to Prime Minister Najib Razak, “this will be the first independent LNG trading terminal in Asia, allowing multiple LNG users to store and trade the product. It will spur the growth of the industry, and help establish Malaysia as Asia's LNG trading hub.”[35]

The Malaysia-Gulf Arab Energy Nexus

Gulf energy producers generally regard Asia to be the “big prize”: it has high rates of economic growth and a burgeoning middle class driving energy demand. More recently, they have come to view Southeast Asia not just as a holiday destination or a stopover on the way to Japan or China, but as a region whose rapid progress and bright growth prospects warrant a greater investment of attention and resources. This naturally begs the question: how does Malaysia’s strategy regarding the O&G sector impinge on Gulf Arab interests? And, how, if at all, have Malaysian-Gulf relations changed in light of global energy market trends, and specifically in response to developments in Malaysia?

Over the past decade, the Gulf countries have invested billions of dollars in Malaysia in various sectors, ranging from real estate to agriculture. Kuwait and Saudi Arabia were the first to do so; next was Dubai. Qatar and Abu Dhabi have recently followed suit, with investments targeting a wide range of projects within the energy sector:

● Aabar Investments, the Abu Dhabi Government investment vehicle, has partnered with the Malaysian firm 1MDB to raise $3 billion for joint investments in energy and real estate projects.[36]

- Mubadala Petroleum, Abu Dhabi’s government-owned O&G producer, agreed earlier this year to swap equity stakes in two deepwater exploration blocks offshore with Royal Dutch Shell.[37]

- Qatar Holding LLC announced in January 2013 that it would invest $5 billion in Malaysia in the petrochemical sector.[38]

- In March 2013, Abu Dhabi agreed to develop a strategic petroleum reserve (for up to 60 million barrels of crude oil) — to be designed, constructed, operated, and maintained for its exclusive use — in Tanjung Piai in Johor state.[39]

- Gulf Petroleum, whose shareholders include Qatar General Insurance and Reinsurance Company, Al-Mana Group and National Petroleum Group, entered into an agreement in July 2013 with local Malaysian companies KNM Group and Zecon to build a refinery, polypropylene plant, and storage facility at Teluk Ramunia, Johor.[40]

Changes have occurred in Malaysia-Qatar energy relations in the area of LNG trade as well. An agreement was reached in 2011 whereby Qatargas committed to supply 1.5 million tons per annum of LNG to Malaysia for a period of at least twenty years.[41] In July 2013, the first-ever cargo of LNG was loaded onto the Seri Begawan at Ras Laffan Port for delivery to Malaysia’s first LNG receiving terminal in Melaka.[42] These imports are intended to buy time for Malaysia to offset declining output from ageing fields with new production, eliminate subsidies, and maintain long-term supply commitments and the sizeable export revenues accruing from them.

Taken together, these cross-regional energy investments and LNG trade arrangements represent a new and promising phase in Malaysia-Gulf Arab relations. Furthermore, they are generally consistent with and supportive of Malaysia’s twin aims of invigorating the O&G sector and positioning the country as a regional maritime energy hub.

At the same time, however, these developments should not be viewed in isolation. Qatar Petroleum’s investment in the Malaysian petrochemicals sector, while significant, is not its only venture in Southeast Asia; for example, it has also purchased a stake in a petrochemical project in Vietnam. Nor is Qatar Petroleum alone among the Gulf Cooperation Council companies in pursuing such opportunities in Southeast Asia and in Asia as a whole. Kuwait Petroleum is participating in an engineering, procurement, and construction project for a refinery in Hanoi for which it will provide feedstock, and is partnering with Total and Sinopec in the development of a refinery and petrochemicals facility in China. Saudi Aramco is involved in a joint venture with Pertamina of Indonesia to process crude oil in East Java, the majority of which Aramco will supply.

Meanwhile, Mubadala Petroleum of Abu Dhabi has started to develop oilfields not just in Malaysia but also in Thailand, Indonesia, and Vietnam in an effort to expand its presence in Southeast Asian markets.[43] And Adnoc’s decision to invest in petroleum storage in Malaysia followed the deal signed several months earlier to lease 6 million barrels of storage capacity near the South Korean port of Yeosu.[44] Both measures give Abu Dhabi greater leverage in marketing its product by allowing for quicker responses to fluctuations in demand and enabling smaller cargoes to be delivered to customers than those typically carried by tanker.

Regarding the LNG trade, Qatargas’s supply agreement with Malaysia was just one of several such deals aimed at diversifying its customer base.[45] The Malaysia deal was followed soon thereafter by similar supply agreements with Japan and Thailand. And Qatar’s first LNG cargoes to Malaysia and to Singapore’s new terminal at Jurong Island arrived at their destinations only a few months apart. That same year, Qatargas also delivered commissioning cargoes to China National Offshore Oil Corporation and PetroChina.[46]

Accompanying the geographic spread of LNG importing countries in Asia has been a growing number of new receiving terminals.[47] Thus, while the LNG trade is a relatively new dimension of Malaysia-Gulf Arab energy relations, it is neither a unique nor an exclusive arrangement. In fact, it is a byproduct of the complex interplay of domestic economic imperatives, changing global energy market conditions, and policy choices—as are Gulf investments in the Malaysian energy sector.

Viewing recent developments in Malaysia-Gulf producer relations through this wider lens, we can see a more complex and dynamic energy market emerging in Asia, as well as a more competitive one on multiple levels: for project investment, access to advanced technology, and availability of skilled manpower, not to mention the marketing, distribution and sale of value-added products.

The exact shape of the new global energy landscape, including Malaysia’s eventual place in it, is far from clear. How will the inherent competition between Singapore, traditionally the hub of all energy trading and storage for Southeast Asia, and Malaysia play out? Will demand growth in Asia be sufficient to support the level of investment and the enhancement of capacity that Malaysia and its neighbors are pursuing? Will Gulf producers continue to diversify their energy trade and investment within Asia, or will they gravitate toward preferential relationships with their Asian counterparts? Could the steps that Malaysia and others are taking perhaps lead to a more flexible regional energy market consisting of multiple trading points, shared storage and terminal facilities, and opportunities for cargo swaps and diversions? Malaysia will play a part in determining, while at the same time itself being bound by, how the regional energy landscape evolves.

Conclusion

The O&G sector is the mainstay of Malaysia’s growth and one of the pillars of the ETP. To date, Malaysia has set ambitious targets and made massive investments designed to boost the O&G sector and leverage its strategic location to become a regional hub for oil storage and trading, oilfield services, and LNG trading.

Leadership has been important. Prime Minister Najib Razak and the institutional structures and relationships forged during his administration (April 2009-present)[48] have played pivotal roles in shaping policy. So too has Petronas, which holds exclusive rights to all O&G engineering and procurement projects and is responsible for all licensing procedures.[49] Their combined efforts so far appear to have paid dividends: Malaysia’s oil output is rising as the result of arresting natural decline in mature fields, while natural gas production is on track to reach record highs.[50] Much has been accomplished. Yet there is also much more to be done in order to transform the O&G sector and thereby help drive the economy to new heights. Recent developments in Malaysia-Gulf Arab energy relations provide a snapshot of how the global energy map is being redrawn and of Malaysia’s progress in positioning itself as a regional O&G hub.

[1] See International Energy Agency (IEA) Executive Director Maria van der Hoeven, quoted in Conglin Xu, “IEA: Southeast Asia Sees Higher Import Dependence,” Oil & Gas Journal, 14 October 2012, http://www.ogj.com/articles/print/volume-111/issue-10a/general-interest….

[2] World Energy Outlook Special Report 2013: Southeast Asia Energy Outlook, http://www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/SoutheastA….

[3] The current major hubs for deepwater oil and gas activities are the United States, Brazil, and Europe.

[4] “The NEM [New Economic Model] Will Be Led by Three Principles,” The Star Online, 31 March 2010, http://www.thestar.com.my/story.aspx/?file=%2f2010%2f3%2f31%2fneweconom…; Malaysia Economic Transformation Programme (ETP), “Oil, Gas and Energy,” http://etp.pemandu.gov.my/Oil,_Gas_and_Energy-@-Oil,_Gas_and_Energy.aspx.

[5] “Powering the Malaysian Economy with Oil, Gas and Energy,” ETP Handbook, 170, http://etp.pemandu.gov.my/upload/etp_handbook_chapter_6_oil_gas_and_ene….

[6] Sean Augustin, “Malaysia to Embark on World’s Biggest Recovery Oil Plan,” New Straits Times, 17 January 2002, http://news.asiaone.com/News/AsiaOne+News/Malaysia/Story/A1Story2012011….

[7] To date, 14 oil fields have been identified under the enhanced oil recovery initiative. Five of these fields lie offshore Sabah and Sarawak, including Baram in Sarawak and St. Joseph in Sabah, while the others are located offshore Peninsular Malaysia, including Tapis and Dulang fields. Risk sharing contracts (RSC) introduced, whereby awarded the contracts and they in turn, would select qualified local partners to develop the RSC areas.

[8] “Petronas Sees 14 Fields Under EOR Scheme Producing Up to 1B Barrels of Oil,” Rigzone, 26 September 2013.

[9] Lysja Emaaj, “Prime Time for Enhanced Oil Recovery,” Business Circle, 7 May 2014, http://www.businesscircle.com.my/prime-time-enhanced-oil-recovery/.

[10] Bilqis Bahari, “Malaysia Has Potential to Become Deepwater O&G Hub,” Business Times, 5 June 2013, http://www.nst.com.my/business/nation/malaysia-has-potential-to-be-deep….

[11] The Murphy Oil-operated Kikeh Block, Malaysia’s first deepwater oilfield (located 110 kms from Sabah), came onstream in 2007.

[12] “Shell Malaysia Starts Production from Gumusut-KakaP Field,” Subsea World News, http://subseaworldnews.com/2012/11/22/shell-malaysia-starts-production-….

[13] “Shell Gives Green Light to Malaysian Oil,” UPI, 5 February 2013, http://www.upi.com/Business_News/Energy-Resources/2013/02/05/Shell-give….

[14] “Oil Found Offshore Sabah at Limbayong-2 Well, Says Petronas,” The Star Online, 17 March 2014, http://www.thestar.com.my/Business/Business-News/2014/03/17/Oil-found-o….

[15] Malaysia Oil Refinery (MOR), Executive Brief, http://www.malaysiaoilrefinery.com/company-profile/executive-brief.

[16] P. Prem Kumar, “PCG-BASF to build RM1.6b aroma plant,” Free Malaysia Today, 4 April 2014, http://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/business/2014/04/04/400051/.

[17] See interview with Dr. Sharheen Madros, the Executive Director of Malaysia Petroleum Resources Corporation (MPRC), The Prospect Group, 29 April 2014, http://www.theprospectgroup.com/malaysia-petroleum-resources-corporatio….

[18] Three such firms are Baker Hughes, Schlumberger, and Technip.

[19] The major foreign operators include ExxonMobil, Shell, Murphy Oil, Hess, and Talisman Energy while the small- to medium-sized operators include JX Nippon, Lundin, and Newfield.

[20] Cheang Chee Yew, “Malysian Gas, Oil Service Firms Focus Overseas,” Rigzone, 25 July 2013, http://www.rigzone.com/news/oil_gas/a/127993/Malaysian_Oil_Gas_Service_…

[21] Jane Xie, “Malaysia to Boost Oil Storage Business as New Oil Terminal Starts on Saturday,” Reuters, 11 April 2014 (Lexis Nexis, 30 April 2014).

[22] Elaine Deng, “Redefining Global Oil and Gas Trading in the Region,” South China Morning Post, 15 June 2013, http://www.scmp.com/article/1046121/redefining-global-oil-and-gas-tradi….

[23] See MPRC, Global Incentives For Trading, http://www.mprc.gov.my/our-businesses/global-incentives-for-trading-gift.

[24] Jeremy Grant, “Malaysia Steps Up Rivalry with Singapore,” The Financial Times, 12 September 2012, http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/1e5f823a-fcb8-11e1-ba37-00144feabdc0.html#axz….

[25] “Government Widens Global Incentives for Trading Programme,” New Straits Times (Malaysia), 13 June 2013, http://www.nst.com.my/latest/govt-widens-global-incentives-for-trading-….

[26] “Powering the Malaysian Economy with Oil, Gas and Energy,” ETP Handbook, Chapter 6, http://etp.pemandu.gov.my/upload/etp_handbook_chapter_6_oil_gas_and_ene…; Elaine Deng, “Redefining Global Oil and Gas Trading in the Region,” South China Morning Post, 15 June 2013, http://www.scmp.com/article/1046121/redefining-global-oil-and-gas-tradi….

[27] These new markets include the Middle East (e.g., Kuwait and UAE), a non-traditional and emerging LNG importing region.

[28] Ahmad Kamarul Yunus, “Petronas Inks LNG Deals with Taiwan’s CPC,” New Straits Times (Malaysia), 7 March 2014 (Lexis-Nexis, May 15).

[29] Paulius Kuncinas, “Malaysia Makes Push for Liquified Natural Gas,” Borneo Post Online, 14 October 2012, http://www.theborneopost.com/2012/10/14/malaysia-push-for-liquefied-nat….

[30] Yvonne Tuah, “Gas: Fueling the Future of Energy,” Borneo Post Online, 20 October 2013, http://www.theborneopost.com/2013/10/20/gas-fueling-the-future-of-energ….

[31] “Malaysia’s Petronas Sells Stake in Canada Gas Project to Sinopec,” Reuters, 30 April 2014, http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/04/30/malaysia-petronas-idUSL3N0NL3….

[32] The terminal is designed for about 5 million cubic meters of total storage capacity. Its jetty facilities are expected to be able to accommodate very large and ultra-large crude carriers. Phase 1A was completed in March 2014 and consists of 25 tanks with a total storage capacity of 432,000 cu m for clean petroleum products. See, for example, Teo Cheng Wee, “US $6.23bn Oil Hub Project,” The Jakarta Post, 27 April 2012, http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2012/04/27/us6238m-oil-hub-project-l…

[33] Jane Xie, “Malaysia to Boost Oil Storage Business as New Oil Terminal Starts on Saturday,” Reuters, 11 April 2014 (Lexis Nexis, April 30).

[34] Petronas approved the final investment decision in April 2014, though the Petronas project has encountered problems acquiring land and relocating residents. John Loh, “Petronas Rapid Gets RM89bil Investment, One-Year Delay,” The Star, 4 April 4 2014, http://www.thestar.com.my/Business/Business-News/2014/04/04/Rapid-to-de….

[35] Quoted in “Malaysia Aims to Become LNG Trading Hub through New $1.3bn Terminal,” Rigzone, 14 September 2012, http://www.rigzone.com/news/oil_gas/a/120699/Malaysia_Aims_to_Become_LN….

[36] Tom Arnold, “Abu Dhabi Link Up with Malaysia,” The National, 18 April 2013, http://www.thenational.ae/business/industry-insights/finance/abu-dhabi-….

[37] April Yee, “Mubadala Petroleum completes equity swap deal with Shell in Malaysia,” The National, 19 January 2014, http://www.thenational.ae/business/industry-insights/energy/mubadala-pe….

[38] Wong, Wei-Shen, “Qatar’s Sovereign Fund Sees Its Investments in M’sia Surpassing US $10bn,” The Star, 30 January 2013, http://www.thestar.com.my/story.aspx/?file=%2f2013%2f1%2f30%2fbusiness%…; “Malaysia Set to Bring Oil & Gas Expertise to Middle East,” AMEinfo.com, 17 March 2011, http://www.ameinfo.com/259488.html.

[39] “Abu Dhabi Signs Petroleum Storage Deal with Malaysia,” Oil Review, 13 March 2013, http://www.oilreviewmiddleeast.com/industry/abu-dhabi-inks-petroleum-st…; “Abu Dhabi in Nearly $7bn Oil Investment in Malaysia,” Reuters, 12 March 2013, http://gulfbusiness.com/2013/03/abu-dhabi-in-nearly-7bn-oil-investment-…; and “Abu Dhabi Agrees Malaysian Investments Worth Millions,” AFP, 13 March 2013, http://www.yourmiddleeast.com/news/abu-dhabi-agrees-malaysian-investmen….

[40] “Oil Companies KNM, Zecon Sign RM17b Projects, Shares Up,” The Malaysian Insider, 27 July 2011, http://www.themalaysianinsider.com/business/article/zecon-knm-shares-ri…; “Gulf Asian Petroleum to Build Refinery, PP Plant, Storage in Malaysia,” Platts, 26 July 2011, http://www.platts.com/latest-news/petrochemicals/singapore/gulf-asian-p….

[41] “Qatargas and Petronas sign Heads of Agreement for long-term LNG supply to Malaysia,” Qatargas, 24 July 2011, http://www.qatargas.com/English/MediaCenter/PressReleases/2011/Pages/HO…; “Qatar Agrees to Supply LNG to Malaysia for 20 Years,” Reuters, 24 July 2012, http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/07/24/qatar-malaysia-lng-idUSL6E7IO….

[42] In 2007, Qatar exported LNG to eight different countries, while just four years later, in 2011, it exported to 23 countries, from the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait to Argentina, the United Kingdom, and Japan. Regarding Qatar’s first-ever delivery of LNG to Malaysia, see “Qatar Sells First LNG to Malaysia,” LNG World News, 22 July 2013, http://qatargas2.rssing.com/browser.php?indx=13953099&last=1&item=5.

[43] Arno Maierbrugger, “Petrodollars from the Gulf shower on Southeast Asia,” Gulf Times, 9 February 2013 (Lexis May 27); and “Total, Kuwait’s KPC Sign China Refinery Agreement,” AFP News, 14 March 2012, https://my.news.yahoo.com/total-kuwaits-kpc-sign-china-refinery-agreeme….

[44] Florian Neuhof, “Abu Dhabi to Invest in Malaysia Oil Storage,” The National, 13 March 2013, http://www.thenational.ae/business/industry-insights/energy/abu-dhabi-t….

[45] In 2007, Qatar exported LNG to eight different countries, while just four years later, in 2011, it exported to 23 countries, from the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait to Argentina, the United Kingdom and Japan.

[46] “Qatargas Holds Meetings to Review Achievements,” Gulf Times, 29 December 2013, http://www.gulf-times.com/qatar/178/details/376003/qatargas-holds-meeti….

[47] Recent additions include the Haizra (India) and Zhejiang Ningbo (China) terminals commissioned in 2013, and the Nusantara (Indonesia) and Ma Ta Phut (Thailand) terminals commissioned in 2012.

[48] Eldon Bell, “Malaysia Sees Role as Offshore Support Hub for Asia Pacific,” Offshore, vol. 72, issue 5 (2013), http://www.offshore-mag.com/articles/print/volume-72/issue-5/malaysia-u….

[49] Mark Arend, “Asia-Pacific’s ‘Significant Location’ for Oil & Gas Services,” Site Selection (May 2013), http://www.siteselection.com/issues/2013/may/ip-malaysia.cfm

[50] “Malaysia’s $30bn Drive Reverses Oil Decline, Boosts Gas,” Reuters, 14 June 2013, http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/06/14/malaysia-oil-idUSL3N0EM2UQ201….

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.