Some three decades into the life of the Islamic Republic, the Iranian regime has yet to devise and implement a coherent national security policy or even a set of guidelines on which its regional and international security policies are based. In relation to the Persian Gulf region and the country’s immediate neighbors, this has resulted in the articulation of regional foreign and security policies that at times have seemed fluid and changeable. Fairly consistently, however, Iranian foreign and national security policies are influenced far more by pragmatic, balance-of-power considerations than by ideological or supposedly “revolutionary” pursuits.

Appearances to the contrary, Iranian foreign and security policies in relation to the Persian Gulf region have featured certain consistent themes, or, more aptly, areas of continued attention as well as tension. The first feature revolves around the broader military and diplomatic position that Iran occupies in relation to the Persian Gulf itself. Equally influential in Iran’s regional diplomacy is what Tehran sees as “the Saudi factor,” namely Saudi Arabia’s posture and pursuits in the region. Iran’s regional security policy, in the meanwhile, is largely determined by the role and position of the United States in what Iran considers its rightful sphere of influence. By extension, for Tehran, questions about Saudi diplomatic and American military positions and intentions bear directly on the nature and direction of Iran’s relations with Iraq and Afghanistan.

Also important are Iranian relations with its neighbors to the south, with a number of whom — namely Kuwait, Bahrain, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) — Iran’s relations have been tense and cooperative at the same time. The most problematic of these have been Iran-UAE relations and the tensions surrounding contending claims by both countries over the islands of Abu Musa and the Greater and Lesser Tunbs. Again, both in relation to Iran-UAE tensions and Iran’s regional diplomacy toward the other Persian Gulf states, the Saudi and American factors, especially the latter, are not unimportant.

Given the steady securitization of the region’s politics since the 1980s, for both Iran and also for the other Gulf states, foreign and security policies are inseparable. Insofar as Iran’s position in and relations with other Persian Gulf states is concerned, the US military presence in Iraq, Afghanistan, and the Persian Gulf, Iran’s dispute with the UAE over the three islands, and the potential for spillover from internal conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan have all combined to create an environment in which security and diplomatic issues are intimately interconnected. At least for the foreseeable future, therefore, any analysis of Iran’s regional foreign policy needs to also take into account its security and strategic calculations.

Despite persistent tensions over the three islands, particularly since 1992, there is another, equally significant aspect to the relationship between the UAE and Iran — the commercial trade between them. According to one estimate, the volume of trade between the two countries, both officially and unofficially, was around $11 billion in 2007.[1] There are an estimated 500,000 Iranian residents in Dubai alone, of whom some 10,000 are registered owners of businesses.[2] Dubai has emerged as perhaps the most significant entrepot used by Iranian businesses in their attempt to circumvent US and Western economic sanctions on Iran, with goods routinely re-exported from Dubai to various destinations in Iran.[3] Not surprisingly, by some accounts Iran has emerged as Dubai’s biggest trading partner.[4] Despite persistent tensions over the disputed islands, therefore, relations between the two remain generally amicable because of their economic and commercial ties.

In many ways, Iranian-UAE relations are emblematic of Iran’s relations with its other Arab neighbors, whether Iraq or Saudi Arabia or, for that matter, the states of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) as a whole. A history of territorial and other disputes, often made all the more intractable by the advent of the modern state and by age-old cultural and linguistic differences, has resulted in deep-seated mutual mistrust and acrimony. At the same time, the two sides have convergent interests. Ultimately, pragmatic concerns and pursuits, rooted in ongoing assessments of Iran’s capabilities and needs, have guided the country’s foreign and national security policies, both in relation to the larger world and, particularly, insofar as the Persian Gulf region is concerned.

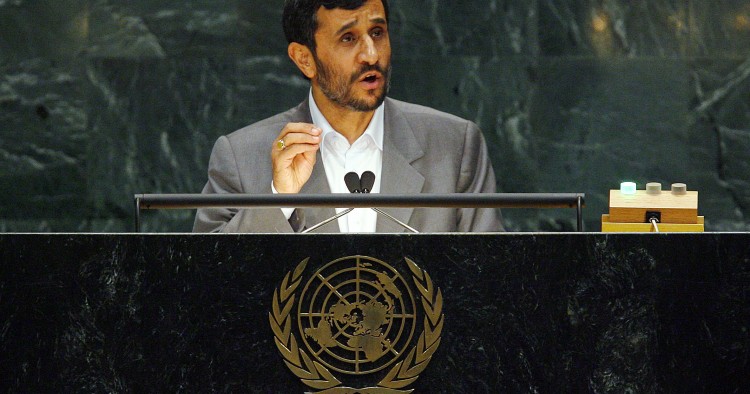

With pragmatism as its primary guiding force, the substance and underlying logic of Iran’s relations with the GCC states, and with the outside world at large, have remained largely consistent since the mid- to late1990s. This is despite the tenure in office in Tehran over the last decade of two very different presidents, one championing the cause of “dialogue among civilizations” and the other a radical rhetoric reminiscent of the early days of the revolution. This begs the question of why, then, did Iran’s relations with the European Union and the United States deteriorate so dramatically during Ahmadinejad’s presidency despite the continuity of his policies with those of Khatami? The answer has to do less with Iranian foreign policy than with larger international developments occurring around the time of changing administrations in Tehran, particularly significant improvements in US relations with a number of European powers that had become strained in the run-up to the US invasion and occupation of Iraq. Meanwhile, Mahmud Ahmadinejad’s tactless speeches and his confrontational personality made it significantly easier to vilify Iran and to present it as “a menacing threat” regionally and globally. In fact, at times Bush Administration officials appeared far more concerned about Iran’s threat to its neighbors than the neighbors themselves. In short, it was not the substance and nature of Iranian foreign policy or its security posture toward the Persian Gulf that changed from Muhammad Khatami to Ahmadinejad. Rather, it was American foreign policy objectives, and with it the evolving nature of America’s relations with its allies in Europe and in the UN Security Council that underwent dramatic changes before and after 9/11 and the US invasion of Iraq.

The future of Iran’s relations with the GCC, therefore, cannot be examined without also considering Iran’s relationship with the United States. It is difficult to imagine US-Iranian relations darkening further than they had during the administration of George W. Bush. Any reduction of tensions between Iran and the United States is likely to be welcomed by the regional states, many of whom have worried, with good reason, about the potential fallout of any open conflict between Tehran and Washington. But many regional actors also worry about the possibility that a warming of relations between Iran and the United States may lessen their luster in Washington’s eyes. A domestically weakened and internationally castigated Iran may be the preferred option of its neighbors, but whether this is a more likely scenario than an Iran which is more integrated into the international community, perhaps led by a different president, depends as much on larger international developments as it does on Iran’s domestic politics and policy preferences. Changes are surely in the offing. What remain to be seen are their degree, intensity, and direction.

[1]. Sonia Verma, “Iranian Traders in Dubai Find Bush’s Rhetoric is Bad for Business,” The Globe and Mail, January 15, 2008, p. 12.

[2]. Sonia Verma, “Bush Rallies Gulf Allies Against Iran,” The Times (London), January 14, 2008, p. 35.

[3]. Eric Lipton, “U.S. Alarmed as Some Exports Veer Off Course in the Mideast,” The New York Times, April 2, 2008, p. 1.

[4]. Verma, “Bush Rallies Gulf Allies Against Iran,” p. 35.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.