Originally posted March 2010

“The current global financial crisis adds further serious complications…we are concerned about the loss of migrants’ jobs; a decrease in migrant remittances; a reduction in Official Development Assistance (ODA) and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and most seriously of all, the stigmatization and scapegoating of migrants tending towards xenophobia.”

— William Lacy Swing, IOM Director General at 106th Executive Committee Session, Geneva, June 26, 2009

The global economy is passing through the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression.

According to the IMF, in 2009, the world economy experienced the biggest contraction in the last 60 years. It is expected that in 2009-10, in the best case scenario, 18 million people will be unemployed globally, and in the worst case, this figure will rise to 30 million. The impact of the crisis has varied by country, sectors, and the degree of linkages of those sectors with the global economy. Before turning our attention to the current crisis, it might be useful to discuss briefly the magnitude and the impact of the past three world financial crises, particularly in relation to labor mobility. Prior to the Great Depression (1929-1934), the doors of the US and the European countries were “open” for migration. In fact, between 1880 and 1920, there was maximum labor mobility in the US and European countries. However, during the Great Depression, international labor migration declined sharply. In spite of pressure to return migrants to their home countries, many of them stayed put, eventually acquiring citizenship in the US and Europe. No large-scale return took place during that time. However, the years following the Great Depression witnessed an emergence of a more restrictive migration policy regime in Western countries.

Since the Great Depression, the world has faced two other significant economic crises. The first of these was the 1973-74 oil crisis, which had a far-reaching effect on labor mobility globally. Indeed, the crisis marked a turning point in the international migration paradigm owing to an end to the European guest worker migration program and the emergence of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries as major new destinations for temporary contract labor.[1]

In 1997, the so-called “Asian financial crisis” broke out, which severely affected the rising Asian “tiger” economies, but did not spread globally. During this crisis, in some countries, migrants were used as “scapegoats” for unemployment; however, these economies quickly realized that the local workforce was not willing to take up the usual “migrant jobs” even during a recession. Therefore, in some Southeast Asian countries, employers sought to prevent migrant expulsion approaches initiated by their governments.

The Global Economic Crisis of 2009 and the Arab Economies[2]

In order to analyze the impact of the current financial crisis on migration in the Arab region, it is of paramount importance to first explore the impact of this crisis on the Arab economies. With the exception of Dubai, the Arab region has a very limited direct exposure to global financial stress and toxic assets. Unlike certain regions, the Arab region had relatively weaker economic ties with US financial markets, and thus was not affected severely when the US financial sector was in turmoil. Nevertheless, there are three indirect channels through which the financial crisis has had a trickledown effect on the Arab region.

- First, there has been a sharp drop in oil prices, from $147 per barrel in July 2008 to around $60 per barrel in mid-2009.[3]

- Second, there has been a contraction in global demand and, consequently, trade and related activities.

- Third, there has been a tightening of the international credit markets, reducing the ability of the Arab countries to borrow. This tightening also has contributed to a decline in the overall level of foreign direct investment (FDI) in the region.

The sectors and areas in the Arab economies that could be affected most adversely in the long run are likely the following:

- Banking and the financial sectors;

- Export sectors, due to a fall in the global demand for goods and services;

- Rise in overall unemployment level;

- Local investment as well as FDI will be negatively affected;

- Fall in the demand for Arab labor in the international market, resulting in a decrease in the level of remittances.

In fact, the impact of a fall in the level of remittances in the region will prove to be a crucial transmission mechanism of the effects of the global financial crisis on the developing countries, particularly labor exporting countries. For instance, in Egypt it is expected that remittances will fall by 16% as a result of the crisis.[4] Globally, remittances have dropped from $305 billion in 2008 to approximately $272 billion in 2009. It is estimated that the level of remittances will rise beginning in 2010.[5]

The overall economic growth in the Arab countries slowed down to approximately 2.5% in 2009 from 6% in 2008. The unemployment level is projected to have risen to 10.8% in 2009 from 9.4% in 2008. In other words, within this year, the region will have at least three million additional unemployed persons. The region, which is usually characterized by high inflationary pressure, has been experiencing disinflationary pressure, with a drop in the inflation rate from 15.8% in 2008 to 14% in 2009. This rate is projected to decrease to approximately 11% by 2010. Nevertheless, this inflation rate is still quite high relative to what economists regard as “acceptable.”

Within the Arab region, it is important to note, there are two different groups of countries, each of which will have experienced somewhat different impacts. One group, oil exporting countries (OEC),[6] generally have more links with the global financial markets. These countries will be unfavorably affected by the fall in the price of oil, as oil and gas contribute almost 50% of their gross domestic product (GDP) and 80% their revenues. In addition, with the tightening of the credit markets, these countries experienced a sharp drop in their net flow, from approximately $890 billion in 2007 to $141 billion in 2009. The growth in real GDP is expected to decline from 5.4% in 2008 to 3.8% in 2010. In the worst case scenario, a prolonged decrease in the real GDP growth of these countries might leave a deep negative imprint on their overall socioeconomic growth.[7]

The other group, oil importing countries (OIC),[8] will have experienced limited direct impacts on their economies. One of the main factors responsible for this is their relatively weak links with the global financial markets. Nevertheless, this group of countries will not remain immune to the negative impacts resulting from a decrease in their overall export level. It is important to note that most of the OIC countries are labor exporters. Therefore, a fall in the demand for their labor abroad, as well as job losses abroad faced by their labor migrants, will lead to a decline in overall remittances. Real GDP growth is projected to have decreased from 6.2% in 2008 to 3.2% in 2009. Similar to OECs, OICs’ total export level will be found to have fallen significantly by the end of 2009. The disinflationary pressures will have been high, with a drop in the inflation rate from 14.4% in 2008 to 9.7% in 2009. The total imports are projected to have fallen by about $29.3 billion between 2008 and 2009. The OIC countries will have lost out heavily due to a decrease in tourism from the nearby Gulf countries as well as from Europe. For instance, Egypt during the first quarter of 2009 experienced a reduction in its tourism income by more than $2 billion and a decline in its income from the Suez Canal by approximately $4 million.[9]

Arab Human Mobility Dynamics

There are three broad mobility “subsystems” or “dynamics:”

- Maghreb labor mobility: This includes Algeria, Morocco, Libya, and Tunisia.

- Mashreq labor mobility: This includes Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen.

- GCC labor mobility: This includes Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and the UAE.

The above categorization arises due to the differences in the characteristics of the population as well as the varied labor market features of these three groups. Simply put, the mobility-related indicators in the Arab region arise due to the following specific causes:

Diversity in population growth: The average population growth rates in the GCC countries ranges from 1.7 to 2.5%. In the Mashreq, this rate is lower (between 1% and 2.2%). It is even lower in the Maghreb (between 1 and 1.9%).

Varied human development experiences: The human development index (HDI) varies across these three groups. They rank anywhere between 33 and 153. The GCC countries do well in relation to the other two groups. GCC countries rank between 33 and 61. Maghreb countries rank between 56 and 126 whereas Mashreq countries rank between 86 and 112. Yemen has the highest rank (153).

Variation in the population pyramid: All three sets of countries are characterized by a large population under the age of 15. In GCC countries, approximately 20% to 31% of the population is under the age of 15; in the Maghreb, this figure ranges between 23% and 30%. The Mashreq has the highest percentage of population (between 25% and 42 %) who are below the age of 15.

Difference in unemployment rates and labor market conditions: There is a labor force of approximately 125 million in the Arab region with an annual growth rate of 2%. The GCC countries have the lowest unemployment rate (1.1-5.2%) compared to the Maghreb (11-15%) and the Mashreq (25-42%). This translates into about 12 million unemployed persons in the region, requiring/pressuring the region to create four million new jobs annually.

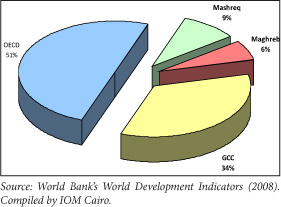

In order to better understand the impact of the economic crisis, we need to look at the geographical distribution of Arab migrants. As the pie charts below show, during the year 2008, 50% of Arab labor mobility was in fact within the Arab region. Thirty-four percent of Arab labor migrants went to the GCC countries while 6% went to the Maghreb countries and only 9% to the Mashreq countries. This distribution has been more or less static in recent decades. Only 50% of the Arab labor migrant force went to the OECD countries in 2008; of these, the majority went to France (52%), followed by other European Union (EU) countries (14%) and the US (10%).

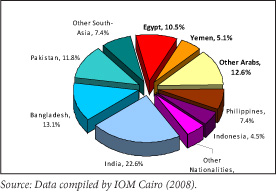

As mentioned earlier, 50% of Arab migrants move within their own region; the majority of these migrants go to the GCC countries (34%). Nevertheless, as shown in the pie chart below, in comparison to the percentage of overseas workers in the GCC countries, Arab workers are not the majority. The greatest inflow of overseas workers to the GCC countries comes from South Asia (54.9%).[10] Arab workers constitute approximately 28.2%, followed by Southeast Asian migrants.

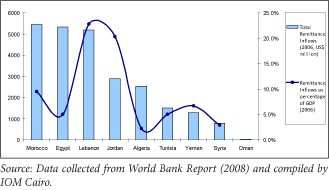

As mentioned at the outset, remittances play a crucial role as a percentage of GDP for many Arab countries, particularly OICs such as Morocco, Egypt, Lebanon, and Jordan. In 2006, all four of these countries recorded remittances of more than 10% percent of their GDP. As can be seen in the graph below, in 2006, the largest inflow of remittances was received by Morocco; however, if calculated as a share of GDP, Lebanon ranked first (23% of their GDP). Furthermore, from the graph below it is evident that although remittances to Syria are the lowest of the countries listed, they nonetheless constitute approximately 3% of GDP. In the Arab region, the GCC countries are typically the ones producing the highest remittances since almost 34% of Arab migrants reside in the GCC states.

The Debate Vs. the Reality of the Impact of the Financial Crisis on Remittances

The Debate Vs. the Reality of the Impact of the Financial Crisis on Remittances

Opinion is divided as to whether the level of remittances will rise or fall as a result of the current financial crisis. Some believe that the level of remittances received by the Arab countries might rise because they think that Arab migrants will be severely adversely affected by the economic downturns in their countries of destination. Since the financial crisis has deeply impacted countries belonging to the OECD group, where half of Arab migrants go, the first employees to be let go when these economies suffer job losses are generally the migrant labor force (temporary workers). Depending on how migrants perceive their conditions of recovery in the destination countries, some might prefer to return to their countries of origin permanently or at least until the crisis is over. Hence, in preparation for their return, these migrants will channel their savings to their countries of origin. Thus, the Arab countries will face an increase in their level of remittance inflows, particularly from countries facing economic hardships as a result of this crisis.

On the other hand, some commentators believe that the level of remittance inflows will decrease as a result of the financial crisis as Arab migrants try to weather the crisis in their countries of destination. They will not return to their countries of origin due to temporary job losses. As a result, these migrants might not be able to remit as much money as previously. They will need to use some of their savings to meet their current and future expenses in the host countries pending the end of the crisis period in those countries.

In reality, the overall global remittance inflows into the countries of origin are projected to have declined from $305 billion in 2008 to $267 billion in 2009 as a result of the crisis.[11] The Arab remittance picture is not much different from the global picture. However, the countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region will not be among the worst-hit developing economies. The overall remittance inflow to the MENA region is expected to decline by 7%, and remittances from the GCC countries to the rest of the Arab region by 9%. Nevertheless, remittance inflows to the MENA countries are expected to pick up in 2010.[12]

While these figures are very appealing, the ramifications of the crisis might trigger more complex dynamics at a regional level, as migration is one of the main forces behind regional economic integration. Moreover, the fall in oil prices might be compounded with the ripple effects of the financial crisis. The World Bank draws attention to the different impacts of a slowdown in construction and financial services sectors. In countries that are more dependent on trade, finance, and real estate, the ripple effects of the global credit crunch will be more manifest than other economies which depend primarily on oil revenues. According to the same report, remittance outflows from Saudi Arabia in recent years have been uncorrelated with oil prices, as many GCC countries are following a long-term strategy of infrastructure development for which they have funding from large reserves accumulated over the years. While it is possible that investment may slow down given the uncertainty of the current global economic climate, it is unlikely that infrastructure investment will stop altogether and that migrant workers will be laid off in large numbers.[13]

At the same time, employers might benefit from resorting to migrant workers (whose bargaining power will be lower during times of crisis) to keep costs low, especially in countries like the UAE and Qatar, where migrants represent more than 90% of private sector employees. Some analysts also suggest that the financial crisis will hit hardest in those countries where demand is led by services (such as in Dubai) as opposed to oil-led economies where investments have been planned according to oil revenues that have been accumulated during previous years.

Impacts of the Financial Crisis on the Migration Patterns in the Arab Region

As a direct impact of the crisis, there has been a reduction in the number of fresh migrant inflows into the advanced economies suffering from economic difficulties. However, the crisis is unlikely to lead to a return of migrants en masse. This is not to negate the fact that migrants might find themselves in precarious situations (such as a becoming a part of the underground economy or becoming “irregular” migrants due to sudden job losses) in certain destination countries.

The direct impacts of the crisis on the employment situations of both the national and expatriate workforces in the Arab states are likely to be limited. The participation of the expatriate workforce in the Arab economies is likely to remain static or decrease negligibly. Hence, the overall inflow of foreign labor into the Arab economies is unlikely to stop as a result of the global financial turbulence. Nevertheless, these economies might experience a shrinking job market particularly in finance, construction, tourism, services, and manufacturing, which might adversely affect the migrant workforce more than to the Arab nationals. There is also the risk that governments might enact more restrictive migration policies, with the unintended consequence of spurring irregular labor migration. Furthermore, there might be a reduction of wages in certain sectors and a deterioration in working conditions affecting both migrant as well as Arab workers.

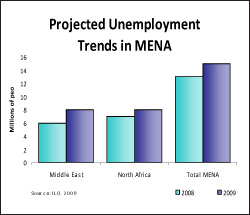

Arab economies have been suffering from the chronic high unemployment of nationals for years. National employment statistics concerning both nationals and migrants are not available. However, according to the International Labour Organization, unemployment in the Middle East region is expected to have risen from 9.4% in 2007 to 11% in 2009.[14] This increase will have resulted in approximately three million workers losing their jobs. Unfortunately, data is too scarce to project how this increase in unemployment levels will impact migrant workers both in origin and destination countries.

The graph below depicts the (projected) changes in the unemployment figures between the years 2008 and 2009. It is amply evident that the Middle East region alone will have had two million new unemployed persons, while the North African countries will have had an additional one million new unemployed persons in their workforce.

Policy and Programmatic Response to Mitigate the Impacts of the Crisis

Policy and Programmatic Response to Mitigate the Impacts of the Crisis

Before designing any policy response, it is important to emphasize the fact that migrants are not a part of the crisis, but a part of the solution. Migrants can be used as an effective tool to aid the economies hit by the present crisis. Furthermore, migrants are foreign workers; hence, treating them with dignity during both the economic boom and bust periods is essential to project a positive image of the host country. It is important to fight the stereotype that migrant workers are only treated well during the economic boom period of the host country. Hence, it is essential to raise awareness within the host countries about the value of the economic and social contributions made by the migrants to these countries. This could be achieved by organizing public seminars and outreach programs on a regular basis. The host country could show its commitment to the rest of the world by discussing this issue and its accompanying concerns in bilateral and multilateral fora.

The countries of origin also have an important role to play during difficult times like this. The origin governments need to devote efforts to ensure that the rights and well-being of their migrants, especially those affected by the economic downturn, are protected. The governments need to enhance the role of their embassies and labor attachés. Finally, there are equally important roles to be played by international organizations in assisting the governments of both the origin and destination countries to help mitigate the adverse impacts of the crisis, as well as to ensure the best interests of the migrant workers.

It is of cardinal importance to understand that regular labor migration channels need to remain open with a view to meeting any continuing demand for migrant workers in the region. There need to be effective bilateral arrangements, along with periodic regional and global dialogue to understand the changes in the labor markets and their ensuing effect on the migration paradigm. Having regular channels of migration also will help to reduce irregular or clandestine human trafficking and smuggling necessitated by the underground economies.

Enhanced reintegration programs for returnee migrants need to be in place to ensure that these workers can put their skills and knowledge into effective use in their countries of origin. Both the host and the origin governments will need to cooperate in order to ensure proper implementation of these special assistance programs (e.g., micro-financing support, etc.) for mutual benefit.

Finally, the Arab Regional Initiatives can play a significant role in addressing the economic difficulties born out of the current financial crisis. Implementation of the Arab Summit Resolution on global financial crisis (Kuwait, December 2008) as well as the recommendations adopted in the Arab Labour Conference (Jordan, April 2009) will help to mitigate the adverse impacts of the crisis on the Arab region as well as to ensure a quick recovery of the affected sectors.

Conclusion

The global economic situation is expected to begin to improve in 2012. However, the initial recovery will be at a rate of growth of approximately 1.9%. It is projected that it will take until 2014 in order to reach the pre-existing level of economic growth (4.8%). This is perhaps the first time since the United States emerged as a hegemon that a recovery of this type is unlikely to be US-led. History might perhaps witness for the first time an economic recovery that will be led by emerging economies such as those of India, China, Brazil, and South Africa. The economic recovery already has begun in these countries, and is expected to be followed by the European countries and the United States.

Migrants offset the structural and the cyclical shortages in the labor markets. Hence, migrants cannot be labeled as a short-term solution. They form an integral part of the labor market in the destination countries and are thus a long-term structural solution for addressing market difficulties. Also, since the structural fundamentals of a market tend to remain unchanged most of the time, migrants will remain an essential component of the post-crisis global economy. In the Arab region, many of the economies are heavily structurally dependent on the migrant workforce. Therefore, it is necessary to avoid a short-term outlook, which would turn the current economic crisis into a migration crisis. As mentioned earlier, the Arab countries are not among the worst hit by the present crisis. Hence, it is important for these economies to engineer solutions to mitigate the negative effects of the crisis rather than disturbing the fundamental fabric of the pre-crisis economy.

[1]. The GCC countries are Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

[2]. Unless mentioned otherwise, all the data appearing in this essay have been gathered by IOM’s Cairo office using OECD, ILO, IMF, UNDP, and World Bank data sources.

[3]. The Daily Oil Prices, http://www.prices-oil.org/daily-oil-prices/daily-oil-prices-22-july-200….

[4]. Data collected by IOM Cairo from the Central Bank of Egypt.

[5]. Dilip Ratha and Sanket Mohapatra (2009). Revised Outlook for Remittance Flows 2009 - Migration and Development Brief No. 9. World Bank.

[6]. OEC countries include Algeria, Bahrain, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Oman, Qatar, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Sudan, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen.

[7]. A few of the OECs encountered some problems in their banking sectors, however, their respective governments stepped in on time and swiftly managed the problem to prevent it from spreading. A positive impact of the crisis on these economies has been a fall in their inflation rates. The overall inflation rate in OECs is projected to decline from 10.3% in 2007 to 8.5% in 2010.

[8]. OIC countries include Djibouti, Egypt, Jordon, Morocco, Mauritania, Lebanon, Syria, and Tunisia.

[9]. Data collected from the Central Bank of Egypt.

[10]. This 54.9% is a cumulative figure obtained after adding the percentages for Pakistan, Bangladesh, India, and other South Asian countries.

[11]. Dilip Ratha and Sanket Mohapatra, “Revised Outlook for Remittance Flows 2009,” Migration and Development Brief No. 9, World Bank, 2009.

[12]. Ratha and Mohapatra, “Revised Outlook for Remittance Flows 2009.”

[13]. Ratha and Mohapatra, “Revised Outlook for Remittance Flows 2009.”

[14]. ILO, Global Employment Trends, January 2009, https://webdev.ilo.org/asia/info/public/pr/lang--en/WCMS_101494/index.h….

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.