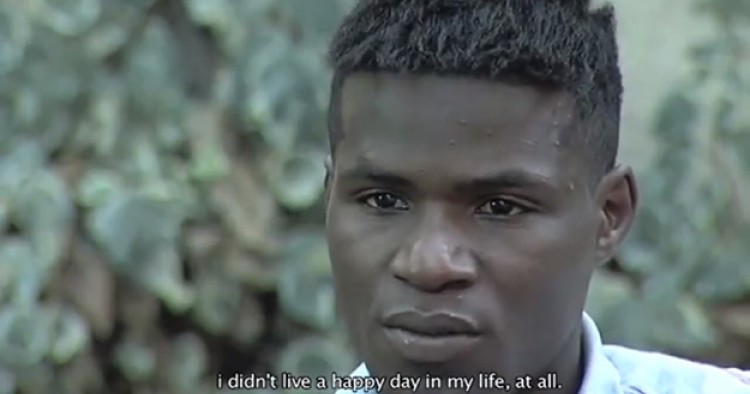

Ismael Mohammed of Egypt recalls the moment he lost his religion. It happened four years ago, at the age of 26, when he heard about the theory of evolution for the first time. He had come across it online by watching YouTube videos and reading all the material he could fit through Google Translate. He sent query emails to evolution scientists around the world, asking them if what they were saying was true. Some responded, sending him the nuts and bolts of Darwin’s work.

“I was shocked. I started walking around like a crazy person, disheveled, unshaven, and confused,” he said by Skype from his home in a small town by the Red Sea.

Shortly after this, he lost his faith in God, and came out to his loved ones as an atheist. Now Mohammed has become something of an atheist preacher, with over 120 episodes on his YouTube channel, Black Ducks, on which he interviews atheists from all over the Arab world and interrogates religious beliefs.

“Aren’t there grammatical errors in the Qur’an?” he asks one of his guests, probing a taboo subject that challenges the widespread belief that the Qur’an is the direct and infallible word of God.

On a second YouTube channel, called Voice of Secularism, he advocates for the separation of religion from the Egyptian state.

Mohammed is part of a larger trend among Arab youth today who are crossing red lines and changing their cultural landscape. In Mohammed’s case, the Internet has been the main catalyst for initiating a conversation among a widening circle of Arab youth.

In a recent piece by Ahmed Benchemsi, the author argues that liberal values have continued to spread in the region since the “Arab Spring,” despite the uprisings’ apparent failures. The Internet is the principal facilitator of this, with a growing presence of groups like Arab atheists and gay rights advocates. “In other words, the Internet, with social media at its forefront, is increasingly part of the daily reality of the everyday Arab citizen—and the conversation on it has a strong liberal flavor,” Benchemsi writes. Benchemsi also cites studies that are starting to look at how Arab youth are transitioning these conversations from cyber space into real life. But researchers do not have to look hard to find that this is already happening, perhaps inadvertently, in the living rooms of exiled and educated, middle class Syrians.

During a recent visit to Beirut, Lebanon, where over a million and up to one third of the small country’s population is comprised of displaced Syrians, many recent arrivals were redefining themselves now that they are dislocated from family, community, and all the social mores that used to govern their behavior. Anonymous and exiled, their new life takes unexpected turns and requires new boundaries. A young unmarried couple cohabitates because they are unable to produce the required documents to marry in a Lebanese court, having left their personal belongings in Syria when they fled in a hurry.

“Rents are expensive when you live on your own, and we’re as good as married because we’re public about our relationship,” they explained during a social gathering at their modest apartment in downtown Beirut. “So the logical conclusion is for us to live together.”

In attendance at the gathering was a young woman from Damascus who is now living with male roommates in Beirut. She said that she never would have lived with strangers had things remained peaceful back home, where the social norm for both men and women is to live with parents until marriage. But now she is on her own and the rest of her family is dispersed all over Syria and the world. Such stories are becoming commonplace among Syrian refugees.

Even in relatively stable Jordan, an emboldened youth is starting to change the ways of an antiquated establishment.

Widad Shafakoj captures this dynamic in her documentary, which was meant as a college project but ended up precipitating changes to the country’s law. Shafakoj originally set out to film abuses in a local orphanage, where the orphans were so neglected that they could not read at the age of 18. But the real red line that Shafakoj crossed was to bring attention to the controversial subject of illegitimate children, who were also housed at the orphanage.

Islamic jurisprudence clearly stipulates how orphans in a Muslim society must be treated. They are the responsibility of the authorities, and although adoption is illegal, guardianship is encouraged. But a guardian cannot change the name of an orphan or consider him or her a blood relative for the purposes of inheritance or marriage. This is because the Islamic tradition holds lineage in the utmost regard.

Thus when it comes to illegitimate children whose parentage is unknown, jurisprudence is murky, and religious authorities in Arab countries have done little to address the issue. Without a system that spells out the responsibility of society toward illegitimate children, and without mechanisms that support desperate mothers, illegitimate babies are often abandoned in a bassinet at a mosque or a public park, where they immediately become wards of the state. They are then stigmatized and grow up as personae non gratae in their own country. In Jordan, like in most Arab countries, the state issues its citizens a national identification card that is based on place of birth and family or clan affiliation. But since abandoned children are of unknown origin, they are issued dubious documents.

“Their national ID number begins with zero zero zero, which makes them stand out, and even the police usually aren’t familiar with it, so often the police accuse them of carrying a counterfeit document and they can’t access government services like health care or education, or even get a job,” said Shafakoj, noting that this problem occurs in other Arab countries as well.

Before Shafakoj could screen her documentary, the Jordanian security apparatus got word of it and panicked. They detained and interrogated for two days the teenagers at the orphanage who Shafakoj had been interviewing. They then approached Shafakoj’s college administrators and demanded that they censor Shafakoj’s film. At some point, Shafakoj found herself at a public event attended by some of the young Jordanian royals such as Prince Ali, and she had an idea. “I figured since I’m already here, I might as well try my luck and approach the prince,” she said. His response was sympathetic. She recalled him telling her, “The trouble with our society is that when we see there’s a problem, we like to cover it up. So I’m giving you the green light to send it to festivals, to screen it anywhere you want.” And indeed, he facilitated the screening at the Jordanian Royal Film Commission, and it made waves. The orphanage was shut down immediately, and all the orphans were transferred to other, better functioning centers. Moreover, the law toward children of unknown origin has recently changed in Jordan. Today, an illegitimate child in state custody can grow up as a full citizen with proper documentation and unfettered access to all public services.

Although Shafakoj has left Jordan for Dubai, she is determined to continue her activism.

“I felt the impact that I made with the orphanage documentary, and I want to keep doing that,” she said, adding that she is looking for places to screen her newest documentary, this one about so-called honor killings of women in Jordan. She captures the new spirit emerging among many of her generation. As Mohammed, the Egyptian atheist preacher put it, change is coming.

“It’s not easy, and we need help,” he said. “But now we have access to books and information online, and [can] learn things that were banned just five years ago. Yes, things are changing.”

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.