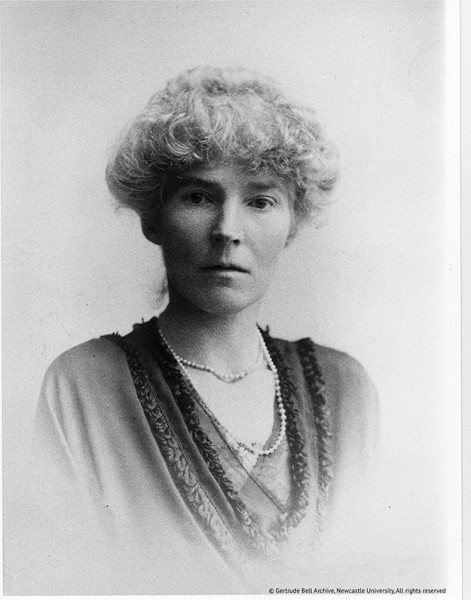

She was a fearless trailblazer who spurned the comforts of Victorian England for a life of adventure and accomplishment, including extensive exploration through uncharted Arabia in the uneasy last days of the Ottoman Empire.

Letters from Baghdad: The Extraordinary Life and Times of Gertrude Bell, a documentary from New York-based filmmakers Zeva Oelbaum and Sabine Krayenbuhl, opened earlier this month in New York City, and will roll out to other major centers through July.

Bell mounted lavish desert expeditions in the years leading up to World War I, managing to penetrate local tribes using her natural ease and charm, cultural awareness and a command of the language, as many of her male contemporaries could not.

The British government eventually recruited her to work as a spy, and she was so in-tune with and connected to the region that she became a power player in post-war negotiations to shape the Middle East, particularly in redrawing the southern border of Iraq. She was not involved in creating the country’s northern borders or the controversial Sykes-Picot agreement.

In the process of her work in building Iraq, Bell was a passionate advocate for involving the local tribes with which she had become so well-acquainted.

“Dearest father, I’m having by far the most interesting time in my life,” writes Bell in a letter home on November 28, 1918. “It doesn’t happen often that people are told that their future as a state is in their hands, and asked what they would like.”

Oelbaum and Krayenbuhl, who met in 2008 working on another documentary, were drawn to Bell as a complex and controversial character, at once warm and arrogant, humble and proud.

She was the first woman to get a first class in modern history at Oxford University before recording 10 first ascents in the Alps, making her the most successful female mountaineer of her time. She then became the first European woman to solo journey through hundreds of miles of Arabian desert. It’s not a surprise that some critics in the United States are calling Bell “the real Wonder Woman.”

“She was very comfortable being the first and being a trailblazer,” says Oelbaum. “She was a very caring humanitarian who loved people.”

Yet though she was often the lone female captured in British diplomatic photographs of the time, Bell was mostly written out of history. One example can be found in the 1983 first volume of William Manchester’s three-part biography of Winston Churchill, The Last Lion, where the caption for a famous photo of Bell, T.E. Lawrence and Churchill identifies her only as a “friend.” And while Bell has been called the “female Lawrence of Arabia” among her growing legions of fans, there are those who believe Lawrence should have been called the male Gertrude Bell.

Yet though she was often the lone female captured in British diplomatic photographs of the time, Bell was mostly written out of history. One example can be found in the 1983 first volume of William Manchester’s three-part biography of Winston Churchill, The Last Lion, where the caption for a famous photo of Bell, T.E. Lawrence and Churchill identifies her only as a “friend.” And while Bell has been called the “female Lawrence of Arabia” among her growing legions of fans, there are those who believe Lawrence should have been called the male Gertrude Bell.

Indeed, as Bell writes after meeting Lawrence, recounted in Letters from Baghdad: “An interesting boy. He’s going to make a traveler.”

The filmmakers spent four years painstakingly pulling Bell’s story together using archival footage, photographs, thousands of letters and other primary documents, and 22 actors as the voices of her contemporaries. The letters in the documentary’s title, many of them written home to her beloved father and step-mother, are brought to life by Oscar-winning Tilda Swinton as narrator.

In 1913, while travelling through what is now northwestern Saudi Arabia, with tribal leaders moving ominously to the north and the south, the danger Bell feels is palpable. To her father, she writes: “I will not conceal from you that there have been hours of considerable anxiety. War is all around us… In Hail murder is like the spilling of milk.”

Bell wrote several books during her travels and also left behind 7,000 negatives of photographs from her journeys, which are now kept with her papers at the Gertrude Bell Archive at Newcastle University.

“What we discovered is that she photographed many ancient sites that ISIS has now destroyed,” says Oelbaum. “So her photographs are among some of the last remaining evidence of some of these priceless and incredible sites, as well as sites in Aleppo and Raqqa that have been destroyed in the Syrian civil war.”

Letters from Baghdad follows the brief and delayed U.S. release in April of Werner Herzog’s feature film about Bell, Queen of the Desert, which premiered at the 2015 Berlinale and stars Nicole Kidman. The film, which earned poor reviews, sidestepped many of Bell’s accomplishments in favor of focusing on her two ill-fated romances.

Not that the romances aren’t compelling: Bell experienced her first heartbreak on a post-university stay in Tehran with Henry Cadogan, a member of the British foreign service. As Cadogan had no money and her father could not afford to float another family, she had to end her engagement to him and return home. Cadogan died nine months after her departure. Later, in her journeys through Turkey and Syria, she fell in love with the married British army officer Charles Doughty-Wylie, who was killed on the battlefield in Gallipoli in 1915 and awarded the Victoria Cross.

Bell had been in poor health when she died in 1926 in Baghdad at the age of 57, but some felt she took her own life with an overdose of medication. She was unhappy at what had become a life of administration, wanted another adventure, and had never found the soulmate she’d yearned for.

“When you think of who she was and who she ended up being, you can’t see her in a marriage,” says Krayenbuhl. “I think that with anything, she gets bored after a while. That’s one thing we learned about her character, she really is someone who is an adrenaline junkie, who needs to be on the go, needs to be on the road.”

Both filmmakers feel Bell’s greatest legacy is in building awareness for the preservation of ancient artefacts and archaeological sites all over the Middle East, particularly through her efforts establishing the National Museum in Baghdad.

In 1922, Bell began personally assembling items excavated by European and American archaeologists who arrived after the war, to stop them being taken out of the country.

The museum opened in 1926, the year in which Bell later died, and is considered to have one of the most important Mesopotamian collections in the world. It was famously looted in 2003 after the U.S. invasion. However, many of the plundered items were returned and, after undergoing a refurbishment, it reopened in 2015.

Bell also helped create schools and hospitals for women in Iraq.

Bell's tendency for open dialogue, and tolerance, and championing other ethnicities in a variety of settings sets a powerful example, particularly for politicians grappling with fear and ignorance today, the filmmakers argue.

“She had a refined and nuanced understanding of the Arab culture in a way that we could really learn from her,” says Krayenbuhl.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.